#4: moral governance and the gendered body in pakistan’s online spaces

Young women and genderqueers are going against the grain to redefine the public space in Pakistan

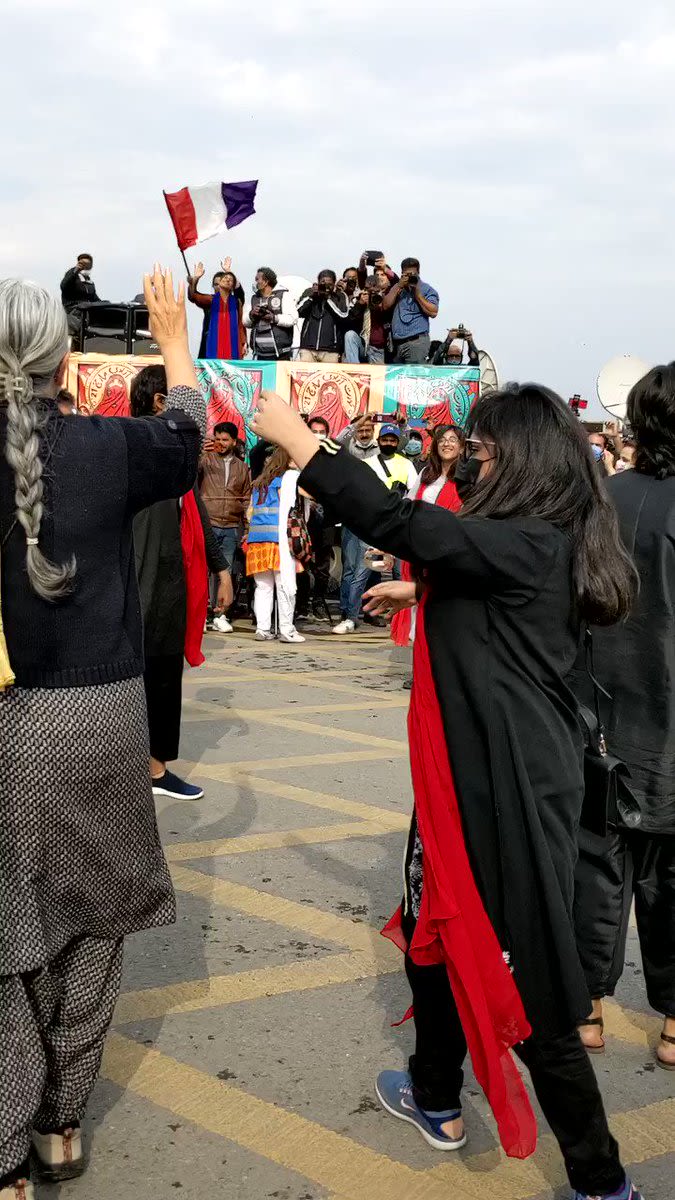

In March 2021, feminists from different walks of life were seen dancing and celebrating the completion of their march to Islamabad’s D Chowk. They danced around joyfully in a circle, with sisterly solidarity and in unison, regardless of where they were from or why they came to the Aurat Azadi March, to celebrate their resistance with verve and abandon.

The air was brimming with joy, confidence and hope, as compagnas of different ethnicities, classes, and genders, older and younger feminists, even children -- people from all walks of life, essentially -- swayed blithely to the rhythm of ‘Daana Pa Daana’ in a bid to claim the space they inhabited, and also to redefine what it meant to be from Pakistan: of Pakistan.

The video capturing their celebration was circulated liberally online soon after. This ‘spectacle’ became one of many targets on the back of the Aurat Marches that were held across Pakistan that invoked the ire of naysayers in the days that followed. A concerted disinformation campaign ensued, in which some of the organizers of the marches were accused of blasphemy on flimsy grounds.

All the women who were seen dancing in front of D Chowk were denigrated and called ‘fahaash’ -- cheap, vulgar, obscene, grotesque -- and hypersexualized in a way they had never anticipated.

-

Two genderqueer artists -- a Pakistani and an American -- were seen posing in front of the steel structured Quaid-e-Azam monument at the Islamabad Expressway, with the words ‘Unity, Faith, Discipline’ at the back, for their upcoming album cover.

Someone decided to share their album cover on Twitter in outrage; a hue and cry was then raised over the vulgarity the musicians were purportedly spreading in society. They were booked under the antiquated penal charge of obscenity soon after. Both musicians were subjected to not only ridicule but also death threats over their innocuous photoshoot, and criminalized merely for exercising their right to freedom of expression.

-

A beela syndicate storms a birthday party to attempt abduction, gang-rape and murder of the guests at the venue as part of an organised campaign of violence and atrocities beelas routinely commit against khwaja sira women and genderqueer men across the nation.

Mehrub Moiz Awan recalled the horrific attack afterwards as she and her friends were trying to escape, and explained how these attacks have been historically coordinated over WhatsApp groups. She demanded justice for khwaja siras in Pakistan, stating that their resistance does not beg for acceptance, nor is it something new: it has stood the test of time, and is an integral part of our shared history.

-

A horde of hundreds of men unleashed themselves upon a TikTokker woman on August 14th, Independence Day, under the shadow of the Minar-e-Pakistan in Lahore. This assault was documented by onlookers with their mobile phones, and this video quickly became viral on social media.

-

There is a tension on display in all these horrifically sinister examples of moral outrage: on one hand, gendered bodies are seen trying to reclaim public spaces that are rightfully theirs, and on the other hand, there are angry detractors who want to teach these bodies an unforgettable lesson. This tension plays out online as well, as feminists are seen being vilified and attacked by naysayers on the daily. Sexualities and genders of all kinds in Pakistan are treated as spectacles and hyper-scrutinized in the virtual realm, which is now shaping the idea of public spaces in Pakistan as people understand them. The internet is now a frontier for battles regarding not just the moral compass but also the cultural politics of the nation.

As the idea of what a public space entails is transforming rapidly because of the presence of the Internet in our lives, we see women and non-binary people being punished merely for exercising their right to free speech. National monuments are fast turning into sites of violence where punishments are meted out to set an example of what happens when feminists demand basic rights. While gender-based violence has always been high in Pakistan, it has seen an exponential rise during the past year, leading many to call what is currently happening in the country a femicide.

However, instead of countering this spate of hostility, the PTI government has ramped up its efforts to moral police Pakistanis and how they present themselves in terms of their gender and sexual expression. The Prime Minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, is often seen claiming that Pakistan is undergoing a moral crisis, as “sex crimes” are on the rise. PMIK is at the helm of the moral panic that has currently gripped the nation, as he blames the rise in gender-based violence and misogyny on the spread of fahashi in society. By repeatedly doling out one troubling statement after another, sometimes in the form of rape apologia, sometimes to blame the spread of “vulgarity” on the adoption of western culture (which he claims to be an expert of) or rising divorce rates (which is more in line with his actual lived experience), and sometimes to condemn mobile phones, Imran Khan is clearly taking notes from history, however erratically. The roots of moral policing were, after all, laid down in the very essence of the idea that the culture of Pakistan needs to be ‘protected’ from falling prey to the vices of western imperialism.

It is clear that no gender identity other than that of the cisheteronormative Sunni Pakistani man can be allowed to exist in the Pakistan the PM foresees. The relationship between the ‘woman’ and the state, on the other hand, is complicated to say the least.

The History of Moral Governance and ‘Obscenity’ in Pakistan

Mainstream conceptions of the quintessential good Muslim Pakistani woman erase the diversity of other gendered experiences in the country, and creates a good v/s bad woman dichotomy through the weaponization of respectability politics. This dichotomy naturalizes heteropatriarchy through the construction of a monolithic (cisgender) national body tethered to Islamic conservatism. ‘Productive’ sexual relations tied to the institution of the family become essential whereas other ‘non-productive’ sexualities and relations are rendered deviant and thus a threat to the country’s reputation.

In fact, legislation and conceptions around respectability date far back: the British empire introduced laws around modesty, indecency and sodomy in the subcontinent to further their moralizing mission of controlling the ‘deviant’ sexualities of indigenous populations. British colonizers criminalized more fluid forms of sexuality and categorized people according to ethnicity, gender and sexuality, in order to create maintainable hierarchies for the allocation of power and resources. Eventually, Pakistani men replaced their colonial overlords; ‘lesser’ genders remained subservient to this imperial order. Hence, the naturalization of heterosexuality is not just a colonial process; it requires complicity on the part of the postcolonial nation-state that shapes productive sexualities to be its very basis. This foundation is then reified through the ongoing process of the sexualization of particular bodies by designating which sexuality is appropriate and acceptable, and which isn’t.

The fact that Pakistan was conceived on the basis of religion shaped existing ‘Muslim’ sexualities significantly in light of the central role of Islam in its conception. Sexuality came to occupy a key position within state discourse and was influenced with particular regard for the institution of family as per the dictates of Islamic and customary practices. Hence, notions of middle class respectability and morality, the narrow vision of “Pakistaniyat”, and colonial ideas of moral governance and obscenity, have shaped Pakistan and now inevitably shape its online spaces. Colonial rule reified the privilege of heterosexual men over all others while historically erasing non-masculinist voices and experiences. This invariably silenced minority groups, thereby subsuming their interests within the broader nationalist construction of the Pakistani state. In particular, Pakistani bodies were gendered and sexualized through a tightly controlled state discourse. Therefore, sexual energies in Pakistan were distilled for the sole task of building an Islamic nation that made no room for diversity.

Women, in particular, eventually became the main targets of the state. General Zia privatized sexual violence with the promulgation of the Hudood Ordinances, thereby eliminating the difference between adultery and rape. Patriarchal controls in the form of clothing restrictions and prevention from participation in public life were now imposed on them. This control over their sexuality eventually became an important component of the Pakistani state’s search for new ideologies to cater to its property-owning, militarized elite, since right-wing propaganda is usually more amenable to mass appeal than a capitalist rationale. Stories of transgender people and khwaja siras, on the other hand, have been completely erased — including the long and unabated history of institutional and societal violence against them.

When women came out on the streets in early 1983 to protest against Zia’s draconian legal regime, religious decrees were passed against them to invalidate their marriages and declare their children illegitimate. The women were called sex workers, blasphemers and foreign agents, and accused of being elitist and oblivious to the issues that ‘real’ Pakistani women experienced on a day-to-day basis. However, the reason why there was no public furore was because social media did not exist at the time.

The British colonial law of obscenity remains in the Pakistan Penal Code to this day, yet still no benchmark or test exists to determine what can be construed ‘obscene.’ To many, our mere presence outside of our homes is obscene; so should all women and genderqueer folks be behind bars for offending the sensibilities of many, for what? Merely existing?

Body Politics and Online Spaces

The complex links between the Pakistani nation-state and the gendered body can be seen in the kind of tension that exists between feminists and their angry detractors in online spaces. As essentialist gender roles have been crystallised for men and women (the only two ‘sexes’ recognized across the board) in Pakistan, any person who challenges stereotypes online is considered to be a transgressor.

Over the past few years, feminists have started talking about the body as a key site of violence and resistance in Pakistan. Conversations regarding the ‘private’ realm have made their way to social media, as important issues pertaining to gender and sexuality in Pakistan are being raised with persistence and bravery.

Interiority, depth, connection and intimacy have become key topics of discussions for feminists during the past few years, and have left the private realm to reach the public. Feminists now publicly speak of affect, through their experiences of desire and intimacy, space and belonging. They also speak of intimacy and agency in the context of family life, and how violence is meted out to women and genderqueers on this basis. Constructing the private domain is not left up to the state anymore, which circumscribes it and simultaneously upholds the family institution as being sacred and untouchable.

The private sphere is not impenetrable anymore; it is now constructed by a public feminist imagination which is at loggerheads with misogynistic ideas espoused by patriarchs and naysayers of gendered experiences. The private territory of self, of personhood, has reached the ‘public’ realm of the internet.

The arbitrary distinction between public and private spaces that was meant to keep people of certain genders and sexualities outside of the national discourse has been dismantled. The notion that families are incubators of nuclear families and model citizens has been dismissed by feminists, only to show discontent and trauma: for that is how women and non-binary people live in this country.

The act of writing and documentation of feminist experiences on the internet reconstitutes the subjectivity of women and non-binary people in radically altering ways. It goes to show that the current feminist movement of Pakistan is neither unified nor stable; it is fragmented, provisional, multiple, and in process.

Consequently, the gendered body has become a national turf as the state attempts to exercise control over it, both online and off. Following this, the national public square is rife with tension: it has become the key site of violence, but also of resistance. The dismantling of the public/private space distinction has led to a reconstitution of gender and sexual subjectivities, and leaves a significant crack in the national imagination of the ‘woman’ subject. The state can no longer earmark the private space as a women's field of work and life, nor presuppose that women are inherently supposed to safeguard the tradition of the inner realm of the domestic or the family institution. The simple dichotomies collapse, and the outliers become a part of the reconstruction of ‘tradition’ and ‘culture’ that the nation state holds onto very closely.

Digital Protectionist Censorship

Having said that, the paternalism of the government of Pakistan has radically altered the online sphere, with regressive internet governance laws and policies on the rise. As if Section 37 of PECA was not bad enough in terms of giving the PTA unchecked power to regulate online content, the rules under it that have been proposed several times by now bode an even more troubling future for Pakistan’s online spaces. Over-regulation of social media platforms for selective purposes seems to be the main agenda of this government, as can also be seen by the continuous bans on TikTok by the PTA, the main reason cited being vulgarity: an excuse often given that indicates nothing but a poor grasp of technology.

TikTok, in fact, is an app that allows women to express themselves freely and challenge middle class notions of respectability that mark a monolithic idea of Pakistani culture which lays the foundation of this country. It shows people, particularly those from lower middle and working class backgrounds, subverting traditional norms and carving a space for themselves that is based on performance and play. The moral panic that has been created over this app only indicates that people here are likely to castigate what they fear and do not understand as it defies traditional norms.

Gendered bodies now represent not only the threat of transgression, but also the need for their control, as the ‘body’ itself has now become the key site of resistance for feminists in Pakistan. National reputational interests always see the gendered body as the repository of honour and virtue, and therefore attach shame and stigma to it. Concerns regarding cultural imperialism therefore seem to begin and end at the body.

The government policing of feminist politics can be seen in the way state institutions have been using fahaashi as a red herring for quite a while now: previously it was PEMRA, now it is PTA. This severely impacts feminist cultural production in Pakistan.

Now we see public monuments in Pakistan fast becoming sites of violence and policing as a response to the visibility of feminist resistance in Pakistan, digitally as well as offline. Such moral panics run deeply through the policies and laws introduced to regulate Pakistan’s digital spaces. The antiquated language around obscenity and morality constitutes one of the key bases for censorship in Pakistan.

Ultimately, the moral policing of the cultural politics of feminism in Pakistan, both online and off, is indicative of the surveillance of young people’s bodies at the precipice of their resistance against regressive notions of statehood — as the state uses them as a battleground to further its own agenda. This is precisely because they are dismantling the hollow conceptions of Pakistaniyat, whereas the nation-state is hell-bent on proving that women and non-binary people who are exercising their right to freedom of expression are anti-national. Young women and genderqueers are going against the grain to redefine the public sphere, and the very idea of ‘publics’, in Pakistan.

Aided by virulent anti-feminist narratives that the right-wing is fomenting, such surveillance then leads to civilising offensives against them, which can be seen in the kind of laws the state is bringing forth in relation to online spaces. This kind of protectionist censorship is, of course, historically grounded; but we are now seeing a new era of censorship, with feminist politics as its battleground.

-

This feature was published in Issue 4 of Digital 50:50 (Moral Policing in Digital Spaces), 2021, helmed by Digital Rights Foundation. It can be read here.